Breaking Down Barriers in International General Practice.

A ground breaking career that brought new ideas and concepts into teaching family medicine across continents but always guided by the principles of personal and continuing patient relationship

Brian McAvoy has been a practising clinician for nearly 50 years,working as a general practitioner, addiction medicine specialist and academic. He has worked with marginalised patients in urban, inner city, rural and remote practices in New Zealand, Australia, the UK and

Canada. He was Foundation Professor of General Practice in Auckland Medical School, Head of the School of Health Sciences at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne and Deputy Director of Australia’s National Cancer Control Initiative. Now retired, he is a Compassionate Companion with Mercy Hospice in Auckland.

“You are so privileged that you are working with people and able to share their thoughts, their aspirations, their fears. You get an opportunity to go into their homes, to be present for all sorts of events throughout their lifetime, in their family’s lifetimes, births, deaths, all sorts of experiences. You are very privileged to be able to do that.”

Watch the video, listen to the podcast, or read the interview.

Brian McAvoy, one of the world’s leading academics in Primary Care, has developed new ideas around the world.

Brian McAvoy: Well, I guess it’s been one of the wonderful privileges of being a GP, and being a medical practitioner, that you have a chance to travel. And, back in the mists of time when I was a student at Glasgow University, it was a six-year course there, but only nine months of teaching and, if you passed your exams you had three months free every year. Some just took that as a holiday but there was always the opportunity to go and work overseas, to do a clerkship if you could scrape together enough money to get a fare to go. You could go anywhere and so I had opportunities every year to go to America, South Africa, Poland, Yugoslavia, and it was a wonderful opportunity to travel and work in another country. And then, after I had graduated and had done my training, things just happened. Serendipity’s been a large part of it. Opportunities came up and I had a chance to go to Canada, and then to New Zealand and Australia, and just enjoy the diversity over the years.

DMacA: Let me bring it back to Canada and you really were a pathfinder because you went to McMaster before evidence-based medicine became so trendy.

BMcA: It was a wonderful opportunity and, again, it was just one of these things. After I had finished the pilot training scheme in Glasgow, teaching general practice was just beginning to come in UK and was really quite exciting, somebody mentioned a place called McMaster and that I should find out a bit more about it. So, I just sent a letter off saying I’d heard about this and I was quite interested in what they were doing, and was there a chance of perhaps coming there. And, I got a letter back saying – yes, sure, come but send us your objectives and we will organize a program for you. I nearly fell over at that! This idea of establishing objectives. They weren’t going to tell me what I was going to do. Suddenly it was back to me to identify what I wanted to do, and how I would do it, and they said- we can give you a teaching fellowship. And you know, that was just an eye-opener. It was wonderful. It ended up 15 months I was over there and it was just incredible. It really was the engine of academic general practice at that time in the mid 70s.

“They weren’t going to tell me what I was going to do. Suddenly it was back to me to identify what I wanted to do, and how I would do it.”

DMacA: If I remember correctly, you came back to Leicester and at that time Leicester was one of the leading postgraduate centres for teaching of general practice in the nascent vocational training schemes.

BMcA: It was the newest medical school in Europe at that time and Marshall Marinker had just been appointed as the Foundation Professor. And again, life’s rich tapestry… in order to fund the fare to go to Canada, and spend a year plus in Canada, I had to get some money together. I had undertaken a locum in general practice down in Northamptonshire before we went. I saw this advert for a little rural dispensing practice in Northamptonshire for a couple of weeks and we thought that would be fun to do and also, we could get some money for our trip. And it just turned out that the two doctors who were working there were growing the practice and were looking for a new partner in the next year or so. It just, sort of, gelled and they said, when you come back from McMaster maybe you might want to come and work here. So that transpired and I started work there.

I got out the atlas and looked to see where the nearest medical school was to find out if there was any chance of getting involved in teaching. Byfield where the practice was, was exactly halfway between Leicester and Oxford. Oxford is a very well established University but general practice really didn’t feature very much. The new set up that Marshall Mariner had begun was quite attractive and I dropped him a line and he said, when you come back from McMaster I’m sure we’ll be able to find some part-time work here. And so I started.

It was a great opportunity because Marshall was open to all sorts of ideas and we were able to bring back some of the things we learned at McMaster – simulated patients, problem-based learning, self-directed learning, evidence-based practice, and we were able to start putting it into practice with the students there. So it was enormously exciting.

DMacA: What an incredible grounding in really innovative general practice. That was so far ahead of its time. So, where did the journey take you next?

BMcA: It took me to New Zealand. I’d been in the practice for seven years and I’d become senior lecturer and was loving it, and getting into research. By then, other centres in UK were developing Departments of General Practice and the whole discipline was growing. A letter popped through the letterbox saying that there was a Foundation Chair being established in Auckland in New Zealand and would I be interested in applying? And that transpired again, serendipitously, because when we were coming back from McMaster to UK in 1977, we decided not go straight back across the Atlantic to the UK but that we would go around the world the long way, and have a month visiting different countries. We had a week in New Zealand, and we had contacts from McMaster who had been there, and so we visited several general practices and saw all around New Zealand in a week. And established a link there. And that’s, I think, why I got sent the letter asking if I was interested. So, again, I threw my hat into the ring and ended up coming out to help set up the new Department of General Practice in Auckland medical school. That again was a wonderful opportunity and provided a link with my old friend Campbell Murdoch who had just been appointed three years earlier as the Foundation Professor in Dunedin in the South Island. He actually taught me surgery in Glasgow when I was a student there. And the wonderful story around that is that I had to come out for a formal interview with the university committee. There was quite a bit of competition but I did get appointed. And then, to my dismay, somebody sent me a cutting from the New Zealand doctor fortnightly newspaper that all GPs got, but the headline was that the Glasgow Mafia had come to New Zealand. And so it was a slightly prickly entry to the world of general practice, having that double whammy of being seen as coming from the NHS, which was the enemy of a lot of the GPs who escaped in earlier years from UK to come to New Zealand, and then this possible conspiracy of appointing me and Campbell.

“Marshall (Marinker) was open to all sorts of ideas – simulated patients, problem-based learning, self-directed learning, evidence-based practice, and we were able to start putting it into practice with the students there. So it was enormously exciting…”.

DMacA: That was quite an introduction. So, these were the early days of publishing in general practice and of course it was a time when people worked both a clinical job and an academic job. Give us a little flavour of the difficulties of balancing those things at that time.

BMcA: It was certainly an unusual thing to be doing and one of the few tensions I had in that first practice where I worked in Byfield, when I was doing a day a week up at Leicester. There were only three of us in the practice, a rural dispensing practice, and we had 5,600 patients between the three of us. We did all our own on-call, all the obstetrics, all the palliative care, and my middle partner wasn’t over supportive of my day each week at the university. He used to say it was my day off from the practice. I’d drive 40 miles up and down the M1, have a whole day teaching, and then come back to being on-call. But, when I’d come back, he’d hand over at six o’clock and say- how was your day off today. But, I had the encouragement of the other part-time GPs in the department and Marshall was an incredible enthusiast and mentor, and he encouraged us to start to do some research. And, that’s where having a practice base, and patients, and just collecting data and starting to dip my toe in the world to research, I was encouraged.

DMacA: So, you’re in New Zealand but clearly you must have had itchy feet because you’ve really travelled way beyond that. Tell us about where you went, the aims and objectives, and the achievements in all these different locations.

BMcA: Again, it’s an extension of what I’ve seen as a student. Opportunities came along when you can go and work in another country, and you see a country from a very different perspective when you’re there working rather than there as a tourist. When I was in both Newcastle and Auckland I had the opportunity to do visiting professorships and external examining in places like Malaysia and Saudi Arabia. I had one amazing week in Saudi Arabia as external examiner there, which was an eye-opener and that was in the early 90s.

“…the title epitomizes the sort of patients that I’ve been involved with over the years in marginalized groups in practices in the city and some rural remote areas where patients lead very difficult lives. As the story unfolded, somebody pointed out, that I had joined those ranks at various stages in my life as well!”

DMacA: You’ve written a book about your experiences and there are very many fascinating angles to it but, tell me what was the experience of writing the book like.

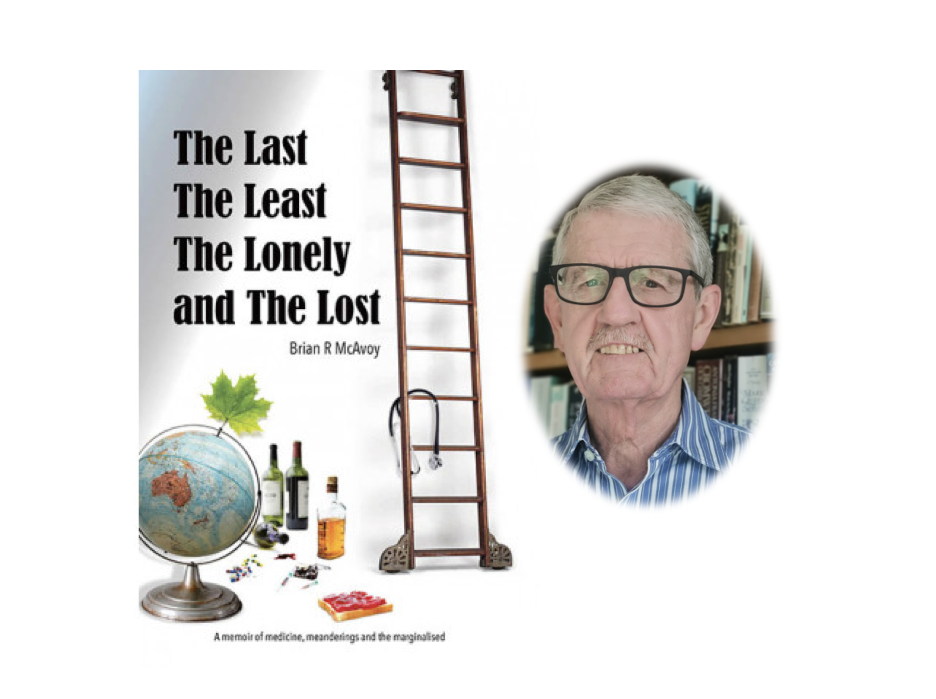

BMcA: It was great fun actually because it was an opportunity to sit down and reflect on things just after I had retired. I had threatened, or promised, to write a non-academic book at some point. I always had the idea that I could write something that was non-academic but, of course, work was the perfect excuse never to do it. But once I retired I was able to do that. The theme through the book is in the title “The Last, the Least, the Lonely, and the Lost” which really epitomizes the sort of patients that I’ve been involved with over the years in marginalized groups in practices in the city and some rural remote areas where patients lead very difficult lives. As the story unfolded, somebody pointed out, that I had joined those ranks at various stages in my life as well!

It just gave me a chance to look at general practice and how things had changed so much over nearly 50 years of clinical practice. And, I had a chance to offer some reflections on what has changed and what hasn’t changed. I’m pleased to be retired now but the book has given me an opportunity to spread the word about general practice and what a wonderful vocation it is. But there are all sorts of issues around now which weren’t there when I started off.

DMacA: I’m very glad you discussed that because I was very taken by the title of the book which describes a lot of the difficulties and sadness and troubles that people have, that patients have, and that we share with them. Reflecting on those 50 years in practice, let me ask you a final question, and that is, what would your advice be to the young GP setting off on an academic career today?

BMcA: Go with gusto. It’s a wonderful opportunity. It’s such an amazing discipline where you have the chance to work with all sorts of people at every stage of their life. You are so privileged that you are working with people and able to share their thoughts, their aspirations, their fears. You get an opportunity to go into their homes, to be present for all sorts of events throughout their lifetime, in their families lifetimes, births, deaths, all sorts of experiences. You are very privileged to be able to do that. You also have the ongoing experience with individuals and with families. So it’s a unique discipline within medicine, with huge challenges but also huge rewards. Be prepared to work hard, be prepared to learn lots of things, and there are quite a few stories in the book about things I learned which certainly are not been taught about in medical school.

I have still vivid memories of the first house call I ever made. The pilot training scheme in Glasgow enabled you to work in a practice for a year. You sat in with the GP at first, and then he sat in with you for a while, and then when it was felt you were capable enough you were allowed to go off on your own for the first house call. Mine was to a house in the unfortunately named Nitshill estate, which was one of the slum estates around Glasgow where life was very hard for a lot of people. This was in the early 1970s. When I arrived at the house, there was this little boy, seven or eight year old, covered in spots and the parents took me through to the bedroom and I took my brand new medical bag and carefully took a thorough history from the parents, then examined the little boy very carefully, ears, nose, throat, chest, heart, temperature, and was confident that he had measles. I put my stethoscope away. By this time most of the extended family had arrived and were all peering around the door into the bedroom to see what the doctor was up to. I stood up and started walking across the room to tell them the diagnosis and what needed to be done, and I noticed there was something under my foot. I looked down and it was a piece of bread with jam on it that had been under the bed and then stuck to the sole of my shoe. I decided it was probably better to just ignore it, and I went across the room walking on my heel. I spoke to the parents and when I got out of the house I was able to scrape it off on the pavement. But you know, it was it was one of those moments that remain with you for the rest of your life.

DMacA: That’s certainly the essence of general practice, those particularly memorable moments that you don’t learn about in medical school.

Brian it’s been an absolute pleasure talking to you. It’s been a privilege because what you don’t realize that, as I trailed through my academic career, I was very aware of your huge contribution to our discipline. Brian thank you very much indeed. It’s been a wonderful chatting to you